Fighting for their Pā

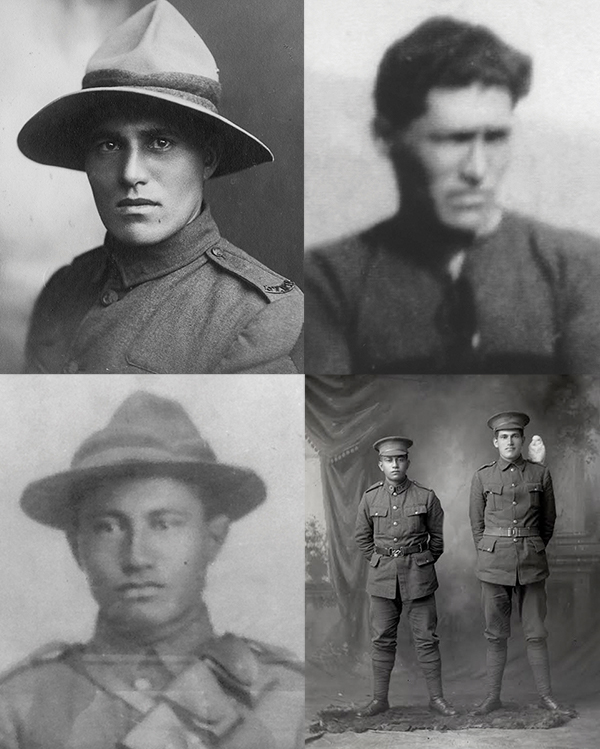

Makaawhio soldiers

Whānau from Makaawhio Pā on the West Coast made a significant contribution to World War One. The small settlement at Jacob’s River had only 13 able bodied men, after discussions amongst the men it was agreed that nine of them would enlist to fight for their country on the other side of the world. The remaining four men would care for the families and tend to all the farming duties. Two of the enlisted men never returned and another two died shortly after returning from war.

Makaawhio, 1903.

Well-known Makaawhio names of those who fought included Te Koeti, Te Naihi and Bannister. Paul Madgwick, who chaired Te Rūnanga o Makaawhio for 15 years, learned much of his whānau history from his uncles and grandmother, the children of Ani Te Naihi, whose brothers left Makaawhio Pā to fight.

She felt sad for her mother. The rest of her siblings had died, and the boys’ father, Wi Katau Te Naihi, died while the brothers were on their way home from war.

Paul describes Makaawhio Pā as an isolated place and suspects this is why so many men left for war.

They had no communication with the outside world. They would have been weeks behind hearing the news. No newspapers, only a ship once a month yet so many volunteered. I guess it was the domino effect maybe. That whole romance of seeing the world.

The nine Makaawhio soldiers, who left for the battlefields of Europe and the Middle East, were Te Koeti Turanga’s two sons and seven grandsons. Paul says Te Koeti Turanga was married seven times and describes him as ‘a bit of a player’.

He remarried when he was well into his seventies. She was a teenage girl, his cousin, Ripeka Patere Tutoko, only about 15 or so. Together they had about 10 children, and two of those boys, the younger ones, volunteered for the war, Pahikore Te Koeti, (baptized as John Butler) and the youngest son, Teoti Te Koeti.

Pahikore, a private in the First Māori Contingent A Company, left New Zealand for Suez on 14 February 1915. His brother Teoti (or George) left nearly two years later for England on 19 January 1917, in the Māori Contingent of the 13th reinforcements.

William (Bill) Bannister, Tuhuru Bannister, Kelly Te Naihi, and Wi Piro Katau and David Bannister.

The seven grandsons of Te Koeti Turanga, and nephews of Pahikore and Teoti, were four brothers from the Bannister whānau and three brothers from the Katau Te Naihi whānau. Paul’s great great grandfather, Wi Katau Te Naihi was married to Hera Te Koeti, the mother of the Te Naihi boys.

Pahikore and Teoti Te Koeti were legendary sportsmen in South Westland. Pahikore had guided many Europeans on their first ascents in the Southern Alps and Teoti was a champion athlete and pole-vaulter. While Pahikore was serving in France with the New Zealand Pioneer Battalion, a wood chopping contest was held in April 1916 between the Māori and French soldiers. The Māori team, which included Pahikore, won by an impressive three minutes. The following month, Pahikore represented New Zealand in the Allied Forces ‘championship chops’ and with his nephew, James Bannister, ‘vanquished the opposition’.

Pahikore Te Koeti was invalided home at the end of the war with lung disease but he recovered after a few years and was able to pick up the axe again. Teoti wasn’t so lucky and after returning home at the end of the war, he died from the effects of gas inhalation.

According to Paul, two Te Naihi boys died serving overseas and the third, like Teoti, died from gas inhalation after he returned home from the war.

Two of the Te Naihi boys, Kelly and Wi Piro enlisted under the family name of Katau. Kelly, a Trooper in the Canterbury Mounted Rifles served in France and died on 18 August 1916, from bronchial pneumonia while on active service. His brother Wi Piro (or Wilson) also served in France but as a member of the 2nd Māori contingent in the NZ Cycle Corps. The brothers are buried in separate London cemeteries.

Paul says the Bannister brothers were lucky to all make it home.

David Huihui Bannister was only 17 and one of the first to go. He volunteered, and had the blessing of parents who would have known he was underaged. He lied to put his age up and signed up in April 1915, as an 18 year old but celebrated his eighteenth birthday overseas in the army. He also volunteered for World War II as a sergeant but didn’t serve overseas. In later years he went to collect his pension and war record, he was a year out, so it caught up with him in the end. He had to convince them that he’d lied about his age at the time.

A fifth brother, George, also volunteered for war service, but he was rejected for being ‘flat-footed’, despite having walked all the way from Makaawhio to the army office in Hokitika. He turned around and walked home again, and a few years later became a fleet-footed mountain guide in South-Westland.

James Bannister was a Lance Corporal with the Canterbury Mounted Rifles enlisting in December 1914. Fighting in Gallipoli, he was shot in the back and later wounded in the hip. On the 27th January 1919 James was discharged as no longer fit for service after four years and 30 days.

According to Paul, this injury didn’t hold James back and he recovered after the war and continued as a champion axeman as well as playing for the Māori All Blacks, who he toured Australia with, in 1923. He carried on sawmilling around Westland and Hokitika and then went to Fiji. He died there with something like malaria.

William Bannister and David Bannister were both builders and helped Makaawhio make a name for itself as ‘the place where waka were built’.

William became a corporal in the Rifle Brigade and didn’t join up until December 1916, arriving in Plymouth on 2 May 1917. He was a bridge carpenter, a builder and boat builder. He built old clinkers for the Bruce Bay sawmill. His brother David, after serving in the Pioneer Battalion as a sergeant and spending 63 days in Egypt and Western Europe, ended up in Greymouth as a builder and boat builder. He built the rescue boat, the first one, the Ivan Talley. Bill (William) worked at the Bruce Bay sawmill and as a bridge builder he worked all around South Westland, opening up the Copeland track. He died at Bruce Bay. He had a bit of a farm after retiring from bridge building and is buried in Hokitika.

Tuhuru Bannister moved to Auckland, married and was killed in a car accident in the 1960s. Paul says the nine men who returned from the war didn’t all go back to Makaawhio Pā immediately, but rather ended up wherever there was work.

"When the men returned from the war, there was no welcome home. When Pākehā diggers came home in town they held a dance, but for Māori there was no marae, no hall. The old marae had fallen down. So no celebrations, just at home, no formal welcome and they came home at different times too."

Of the boys that went off to war at least four were champion wood-choppers and they picked it up again when they came home. In the 1920s a wood-chopping event was held in the Greymouth Town Hall, and a champion axeman from Australia came and Butler (Pahikore) cleaned up that as well. He continued that until he was quite old.

Pahikore and others from Makaawhio played a major part in constructing the Copeland Track and the Hermitage Hotel. One legendary feat of his was to walk the Copeland Pass from the Hermitage to south Westland in 15 hours before the track was built. It is now a three day walk on the track.

Pahikore Te Koeti started in the saw mill at Hokitika and eventually made his way back down to Bruce Bay, where he had a silver-pine cutting business. That’s kopara, used for fence posts and telephone posts, and it was a thriving business right through to the 1950s. My father worked for him, for Butler, cutting the posts with an old broad axe, by hand, for many years.

Paul says after the war the main employment for the men was mountaineering as guides, which was a lucrative career. Because the soil was poor and the reserves were not large enough, sustenance farming was not an option.

The saw mill came along in the 1930s and there was work cutting the timber off the Māori reserves. It saved the place. 80-90 percent of the workers were whānau. But it only lasted less than 10 years when the bridge washed out and it was deemed uneconomic to repair. So the owners closed it. Eventually everyone moved out although some stayed around Bruce Bay.

About a dozen families stayed living at the pā until the 1970s but a lack of employment forced whānau to move on. According to Paul most ended up in the Hokitika area.

The war had a huge impact on that little pā without (their contribution) I reckon Makaawhio would be a different place today.

For immediate whānau members wishing to have their own copy of the full video, please contact Whakapapa Ngāi Tahu on 0800 KAI TAHU (0800 524 8248).